There’s a widespread view that Australia has a six-star minimum standard for home energy efficiency. I was taught this, and was of this view for many years. However, I’ve since learned that it is simply not the case.

This article will help you appreciate the misunderstood and complex fundamentals of Australia’s home energy-performance requirements.

2020-08-31

by Richard Keech

In the conversations around home efficiency in Australia, you very often hear that a rating of six stars is the minimum efficiency standard. And with that in mind, a few years ago I was giving a presentation on home energy performance, and repeated something I’d learned in my studies:

A six-star home is the worst-performing house you can legally build in Australia.

A knowledgeable building designer in the audience took me to task and told me I was mistaken. He said it was legal and common to build homes that performs worse than six stars.

It’s apparent that the myth about the six-star minimum standard persists. This article is an attempt to address that.

The Code

Before we can explain why we don’t really have a six-star minimum standard, we need to understand some background about how building construction is regulated here in Australia. The way we’re required to build our homes is subject to the requirements of the National Construction Code, or NCC. Given that building standards are really a state responsibility, the fact that we have a national code is a credit to federal cooperation. The NCC sets the national template standard, and allows for state-by-state variations and carve outs for specific things.

The NCC is a large, three-volume set and also includes the plumbing code as Volume Three. It’s updated every few years. The 2019 edition is the latest version.

Volume Two is the part that applies to homes. Within Volume Two, the energy-efficiency requirements are in Section 2.6, as part of the so-called ‘performance provisions‘, and Section 3.12, as part of ‘acceptable construction‘.

Ways of satisfying the code

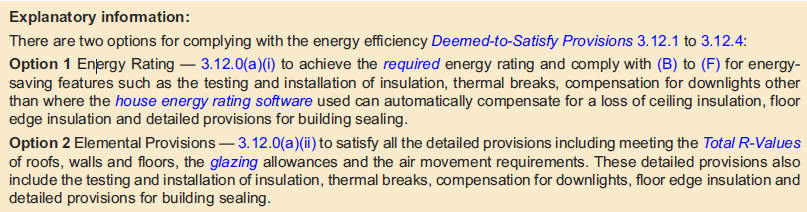

The code gives a building designer a number of different alternative ways to comply with the energy-efficiency requirements. The builder/designer can choose the pathway that suits them best. The alternatives pathways for compliance are:

- Energy ratings (this is where the star rating applies) as per 3.12.0 (a)(i); or

- Use of elemental provisions as per 3.12.0 (a)(ii); or

- Performance solutions, as per A2.1; or

- Verification using a reference building as per V2.6.2.2.

The choice of energy rating, or elemental provisions, is shown as per this excerpt of NCC Volume 2, Section 3.12:

Energy rating

If the designer chooses the ‘energy rating’ pathway, then star ratings apply. However, even in those cases, it still doesn’t follow that a six-star minimum always applies.

Five stars – tropical. The NCC says a five-star minimum standard is sufficient when:

- in climate zones 1 and 2 (i.e. tropical and subtropical); and

- there’s a suitable outdoor living area with ceiling fan.

Five stars – SA. There is a state-specific variation for South Australia such that five star designs are OK for:

- some local government areas only (think outback SA); for

- small dwellings (up to 60m2); and

- with lightweight construction and raised floors.

It’s actually a little more complicated than this but this is close summary (refer 3.12.0.1).

Elemental provisions

Applying the elemental provisions approach means that instead of having a star rating, the building design must tick all the boxes from a whole lot of minimum requirements that relate to different aspects:

- building fabric (3.12.1);

- glazing (3.12.2);

- sealing (3.12.3);

- air movement (3.12.4).

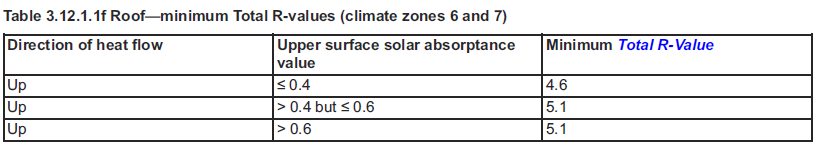

One of the most fundamental elements of achieving thermal performance is using ceiling insulation. For the elemental-provisions pathway, the minimum insulation levels are specified in lots of tables based on climate zone. For example, for Climate Zone 6 (which covers Melbourne), the ceiling insulation requirement is as shown below:

For buildings using this pathway, no star-rating certificate is required. Note that these R values are ‘system’ values, and include the underlying insulation level of the structure (which varies depends on the type of structure).

VURB

The ‘verification using reference building’ (VURB) approach (Volume 2, Section V2.6.2.2) is like the elemental provisions approach but has a slightly different, and overlapping set of minimum requirements. It has the same requirements for ceiling insulation as for the elemental provisions approach.

For buildings using this pathway, no star-rating certificate is required.

Performance solutions

An uncommon pathway for compliance with the code is the ‘performance solution‘, sometimes used for architectural designs which don’t easily comply with any of the other pathways. This approach involves checking the design against all the separate performance requirements of the code and demonstrating that the design satisfies every one. It requires a lot of work.

How many homes don’t get star ratings?

The report of the National Energy Efficiency Building Project (Herrington 2014, pp41) says:

“[elemental provisions] may be more commonly used for lower budget projects (and certainly for smaller renovations and additions), while modelled solutions appear to be more common for larger or more up‐market developments”

In my own experience, it’s common to see a minimal-compliance approach, i.e. builds where it seems that corners have been cut, and where there has been the least possible done to achieve nominal compliance with the energy-efficiency requirements of the code.

CSIRO keep convenient statistics of count of star rating certificates vs number of building approvals. It paints a very interesting picture. On average, across the country there are about three star-rating certificates issued for every four homes built. In order, the state proportions are (where 100% means one star-rating certificate per home building approval):

- TAS (106%);

- VIC (102%);

- NT (93%);

- NSW (85%);

- ACT (79%);

- QLD (63%);

- SA (37%);

- WA (20%).

The proportions above 100% suggest that either:

- sometimes multiple certificates are issued prior to construction; or

- sometimes a planned building with a certificate does not proceed to construction.

That being the case, the low proportions in SA and WA are probably over statements of the actual proportion of homes with a star-rating.

Star rating vs actual performance

A star rating is a promise. It promises that:

- if the thermal model is an accurate reflection of the design; and

- if the home is built as per the design; and

- if there are no changes to the as-built home that impact the performance; and

- if window coverings are used as assumed in the model; and

- if windows are operated (opened and closed) by the occupants when appropriate for thermal comfort; and

- if the neighbouring context (buildings and trees etc) remains as modelled; and

- the occupancy of the house is as assumed in the model; and

- the weather experienced is the same as the average climate,

then the home will stay comfortable using no more than the amount of energy predicted in the model.

So, there are a lot of assumptions. The truth of some of these assumptions depends on the good faith and common sense of those involved in the design, build and maintenance of the home.

Despite all these assumptions, star ratings are a valid and very useful way of benchmarking design performance.

Misleading practice

Sometimes builders promote their builds in ways that are misleading with regards to energy performance. They may imply that a NatHERS rating of six stars represents high energy performance. The NatHERS rating system is not like hotels where six-star means luxury high-end. NatHERS is a ten-star scale, and six-star designs represent mediocre energy performance.

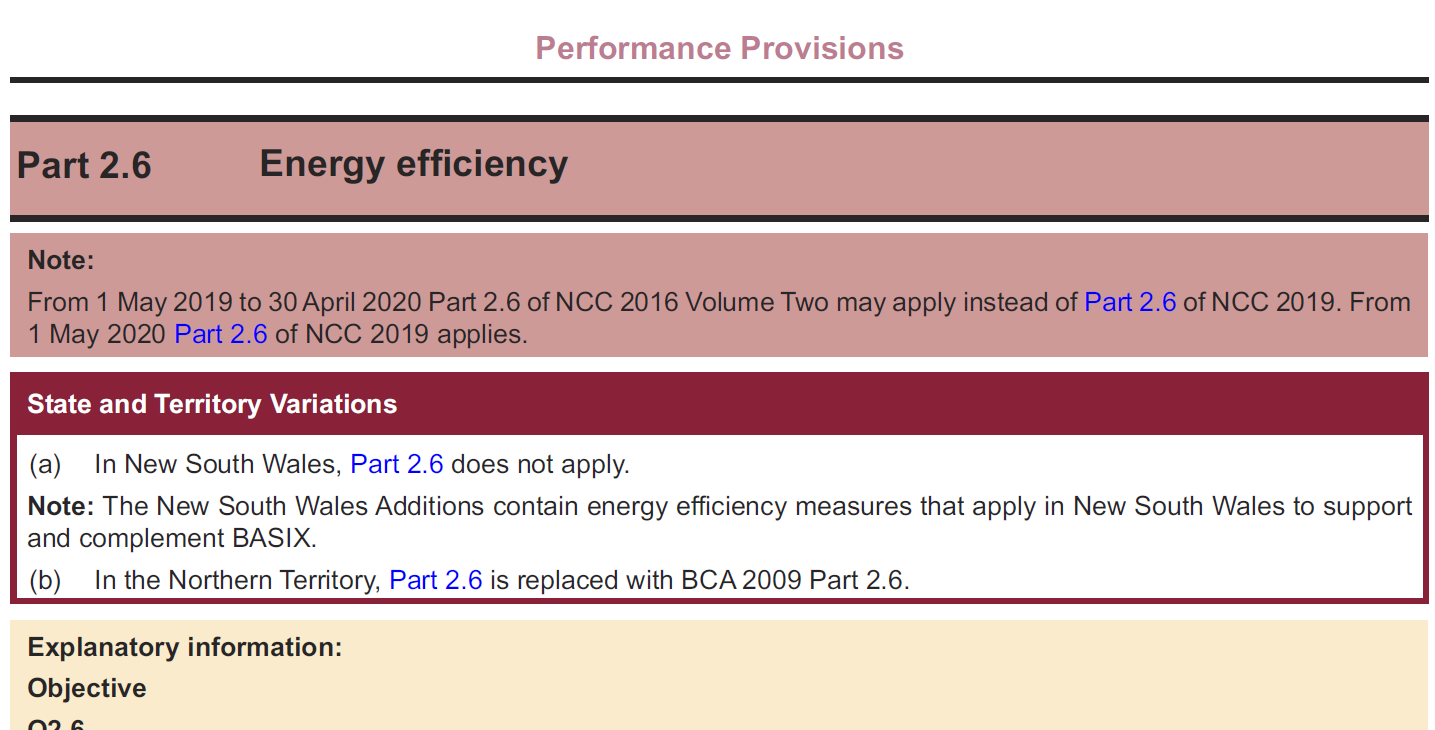

NSW don’t do NatHERS star ratings

Another key reason why the six-star narrative is misleading is that in NSW – our most populous state – NatHERS star ratings don’t apply at all. As the excerpt below shows, in NSW, a separate system called BASIX applies instead of Section 2.6 (Energy Efficiency) of the NCC. BASIX does have its own thermal performance requirements which do use the same energy rating software as NatHERS. However, the ten-star performance rating scale does not apply.

When homes don’t meet their star rating

Having a six-star rating is one thing. Actually achieving it is another. The star rating is issued on the design, not the build. The build, in theory, should faithfully reflect the design. Unfortunately, there are commonly seen ways in which the actual thermal performance falls short – sometimes by a large margin. Common issues relate to key elements not meeting their intended performance:

- insulation

- glazing

- draught proofing.

I’ll blog separately about the specifics. However, the take-away message is, even if a new house has a six-star rating, it probably falls short of this in reality.

The path to 2022

It’s also worth mentioning that energy performance requirements under the NCC are updated periodically, and that there is a lot of work going on behind the scenes for a major update of the NCC in 2022. So watch this space.

Conclusion

Australian homes, as built, are mostly not achieving six-star performance. Being able to avoid six-star standards is not a loophole. The NCC is quite explicit about the different pathways for compliance. I think the misunderstanding about six stars just reflects a widespread misunderstanding about what the code requires.

If you’re building a new home, then you should be aware of how your designer/builder intends to comply with the energy performance requirements of the code.